Just weeks without the deadliest wildfire in modern U.S. history ripped through the coastal town of Lāhainā, Native Hawaiian taro farmers, environmentalists, and other residents of West Maui crowded into a narrow priming room in Honolulu for a state water legation hearing.

The chorus of criticism was emotional and persistent. For nearly 12 hours, scores of people urged commissioners to reinstate an official who had been key to strengthening water regulations and to resist corporate pressure to weaken those regulations. One without another, they uncomplicatedly and deliberately delivered scathing criticism of a developer named Peter Martin, calling him “the squatter of evil in Lāhainā” and “public enemy number one.”

One person summed up the mood of the room when he said, “F— Peter Martin.”

More than 100 miles yonder on Maui, Martin followed parts of the hearing through a livestream on YouTube. Despite the waterflood of criticism, he wasn’t upset. He wasn’t plane surprised. Without nearly 50 years as a developer on Maui, he’s used to public criticism.

“When you’re virtually a gang of people, a mob, the commissioners just listen to the mob, they don’t listen to reasoned voices,” Martin told Grist. “I’m not comparing these people to Hitler; I’m just saying Hitler got people involved by hating, hating the Jews.”

Martin, who is 76, has long been controversial. He moved to Maui from California in 1971 and got his start picking pineapples, teaching upper school math, and waiting tables. Surpassing long, he began investing in real estate. His timing was perfect: Hawaiʻi had wilt a state just 12 years earlier, and Maui’s housing market was booming as Americans from the mainland flocked there. By 1978, local headlines were bemoaning the upper price of housing, and prices only went up from there.

Developer Peter Martin told the New Yorker that protecting water for Native Hawaiian cultural practices was “a crock of shit,” and that invasive grasses and “this stupid climate transpiration thing” had “nothing to do with the fire.”

Martin points to a map of West Maui, indicating an zone where he hopes to build homes. Next to him is his Bible, which he often quotes in conversations and emails. Cory Lum / Grist

Over the last five decades, Martin has made millions of dollars off this real manor boom, towers a development empire on West Maui and turning hundreds of acres of plantation land into a paradise of palatial homes and swimming pools. He owns or holds interest in nearly three dozen companies that touch scrutinizingly every speciality of the homebuilding process: companies that buy vacant land, companies that submit minutiae plans to local governments, companies that build houses, and companies that sell water to residents. His real manor brokerage helps find buyers for homes built on his land, and he’s plane got a visitor that builds swimming pools.

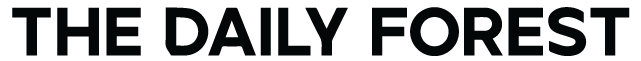

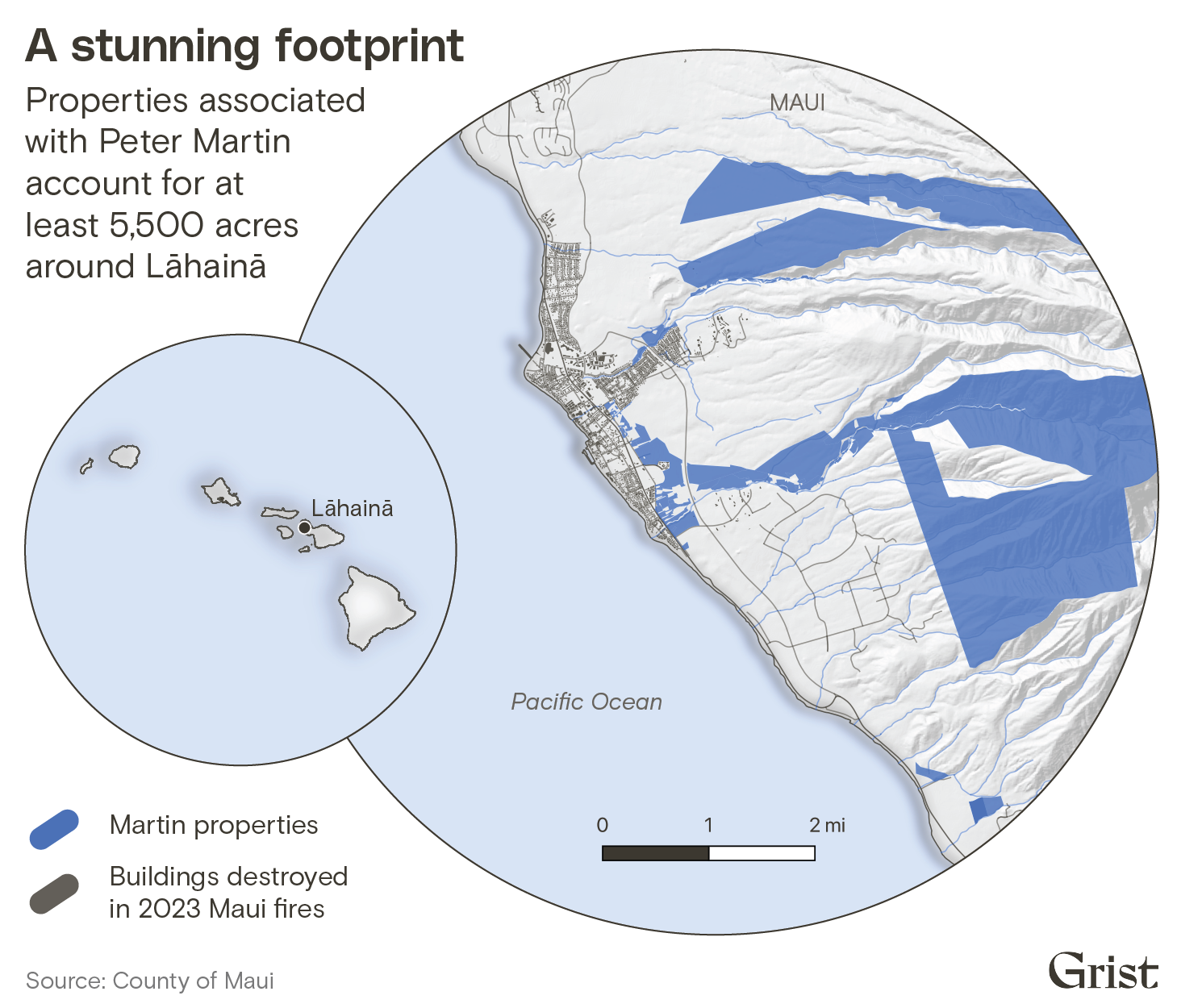

Companies associated with Martin own increasingly than 5,500 acres of land virtually Lāhainā, equal to an wringer of county records, making him one of the area’s largest private landowners, and his web of businesses wields immense influence in West Maui, which is home to well-nigh 25,000 people. He drives his white Ford F-150 virtually the island with a large, woebegone Bible on the part-way dashboard and peppers his conversations and emails with quotes from Scripture or libertarian economist Milton Friedman. He once served on the Maui County salary commission, where he helped determine pay for elected officials and county department heads, and he has donated $1.3 million to the Grassroot Institute of Hawaii, a libertarian think tank that has fought Native Hawaiian sovereignty. So wide-stretching is the reach of his land empire that the writ part-way for the response to the August wildfires is located on land owned by a visitor in which he has a stake.

Development on Maui, where the median home price now exceeds $1 million, often sparks controversy, and Martin is far from the only builder who has inspired opposition. But his staunch ideological transferral to self-ruling market suffrage and Christianity, coupled with his companies’ persistent pushback versus water regulations intended to protect Native Hawaiian rights, has evoked particularly passionate distaste among many locals. “F— the Peter Martin types,” reads one bumper sticker spotted in Lāhainā.

And that was surpassing the wildfire. Just two days without the outbreak of a blaze that would go on to skiver 100 people, fueled in part by invasive grasses on Martin’s vacant land, an executive at one of Martin’s companies sent a letter to the state water commission. Glenn Tremble, who works for West Maui Land Company, wrote that the company’s request to fill its reservoirs on the day of the fire had been elapsed by the state. He moreover asked the legation to loosen water regulations during the fire recovery.

“We watchfully awaited the morning knowing that we could have made increasingly water misogynist to [the Maui Fire Department] if our request had been immediately approved,” he wrote.

Tremble’s letter unsaid that a state official key to implementing local water regulations — and the first Native Hawaiian to lead the state water legation — had impeded firefighting efforts. He soon walked when the claim, but his first letter had firsthand effect. The state shyster unstipulated launched an investigation into the official, the governor suspended water regulations, and the official was temporarily reassigned. Critics saw it as an struggle to capitalize on the grief of the polity for profit.

It didn’t help that within weeks, when the Washington Post asked well-nigh the role the invasive grasses on Martin’s land played in the mortiferous wildfire, Martin said he believed the fire was the result of God’s anger over the state water restrictions.

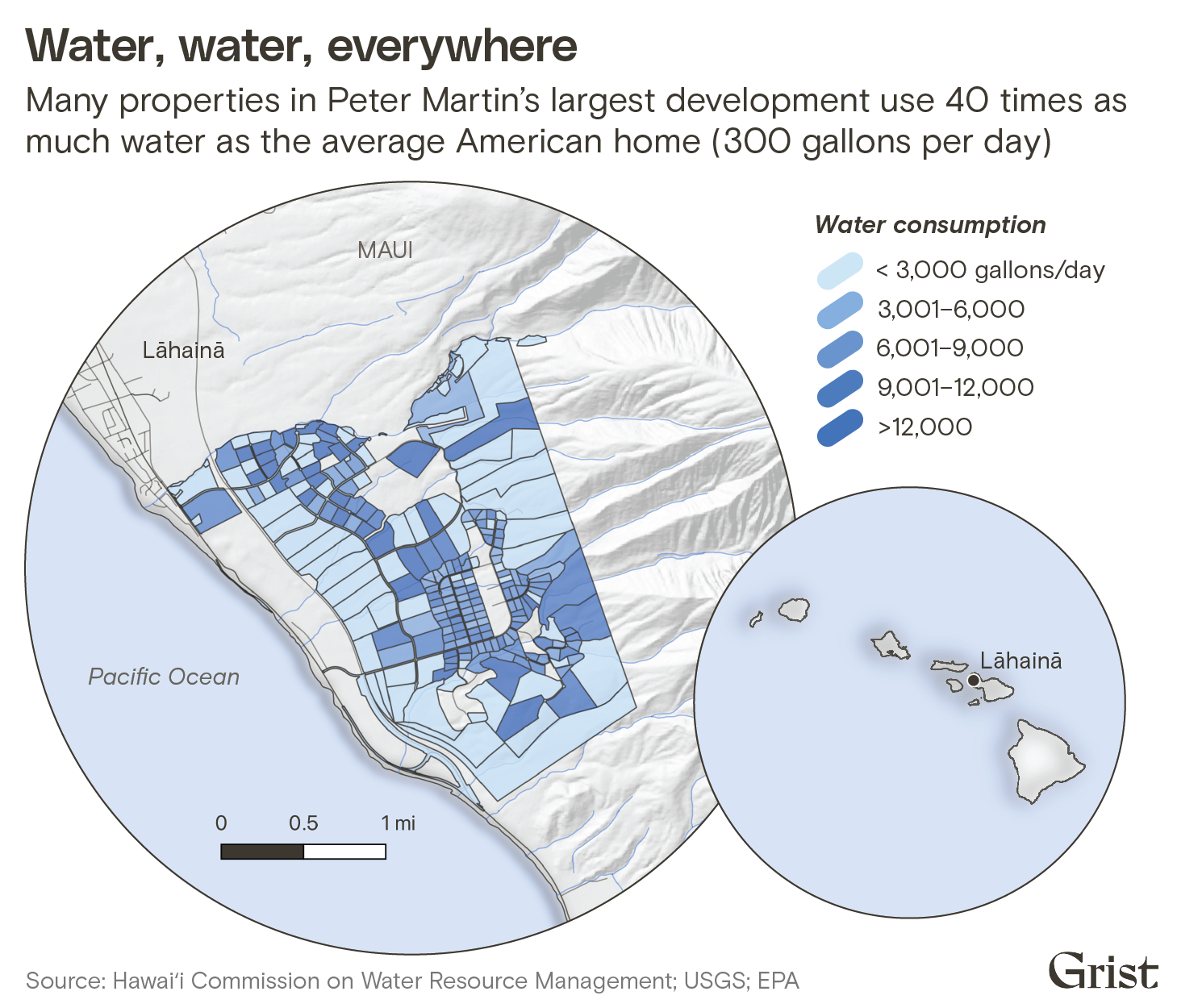

Most people in West Maui get water from the county’s public water system. But Martin-built developments such as Launiupoko, a community of a few hundred large homes outside of Lāhainā, yank their water from three private utility systems that he controls, siphoning underground aquifers and mountain streams to fill swimming pools and gargle lawns. Increasingly than half of all water used in the Launiupoko subdivision, or virtually 1.5 million gallons a day, goes toward cosmetic landscaping on lawns, according to state estimates. Just over a quarter is used for drinking and cooking.

The scale of this water usage is stunning: Equal to state data, Launiupoko Irrigation Visitor and Launiupoko Water Visitor unhook a combined stereotype of 5,750 gallons of water daily to each residential consumer in Launiupoko, or scrutinizingly 20 times as much as the stereotype American home. The minutiae has just a few hundred residents, but it uses scrutinizingly half as much water as the public water system in Lāhainā, which serves 18,000 customers.

Martin says he didn’t set out to make Launiupoko a luxury development, but that its value spiked without Maui County imposed rules that limited large-scale residential minutiae on agricultural land. Martin’s minutiae was grandfathered in under those restrictions, and demand for large homes crush up prices in the area. He says criticism of swimming pools and landscaped driveways is rooted in envy.

“People come over and make their land trappy by using water,” he said.

Martin moreover maintains that there’s increasingly than unbearable water for everyone, but that doesn’t seem to be the case. Yearly precipitation virtually Lāhainā declined by well-nigh 10 percent between 1990 and 2009, drying out the streams near Launiupoko, and now Martin sometimes can’t provide water to all his customers during dry periods. The underground aquifer in the zone is moreover oversubscribed, according to state data, with Martin’s companies and other users pumping out 10 percent increasingly groundwater than flows in each year on average. Climate transpiration could exacerbate this shortage by worsening droughts withal Maui’s coast: Projections from 2014 show that yearly rainfall could decline by virtually 15 percent over the coming century under plane a moderate scenario for global warming.

In response, the state water legation has intervened to stop Martin and other developers from overtapping West Maui’s water, setting strict limits on water diversion and fining his companies for violating those rules. Last year, the state took full tenancy of the region’s water, potentially jeopardizing the future of Martin’s luxury subdivisions and making it harder for him to build increasingly in the area.

Now, though, Martin is poised to play a key role as West Maui recovers from the Lāhainā wildfire, which destroyed 2,200 structures, including six housing units Martin had developed. Nine of his employees lost their homes. As of early November, increasingly than 6,800 displaced people on Maui remained in hotels or other temporary lodging. Millions of dollars in federal funds are expected to spritz into the state for reconstruction. Martin, with his dozens of minutiae companies and thousands of acres of vacant land, is perfectly positioned to build new homes. And his concerns well-nigh water regulations slowing minutiae may find a increasingly sympathetic regulars as local officials seek to write a post-fire housing crisis.

Moreover, he is itching to build. Surpassing the fire, county and state officials were shooting lanugo most of his new towers proposals tween a snooping well-nigh overdevelopment, plane the ones that Martin pitched as affordable workforce housing. Martin thinks he can mitigate West Maui’s fire risk and its housing slipperiness by getting rid of the barriers that prevent developers like himself from towers increasingly houses with irrigated farms and untried lawns.

“What I just want is the water to be worldly-wise to be used on the land, which God intended it to,” he said.

Daniel Kuʻuleialoha Palakiko doesn’t know what deity Martin is referring to.

“Ke Akua is a God of love and restoration and well-healed life,” he told the water legation during September’s hearing, using the Hawaiian word for God. Palakiko had flown to Honolulu with many other Maui residents to urge the state officials to uphold their responsibility to protect water.

Palakiko doesn’t take his land, or water, for granted. He was a teenager in Lāhainā in the 1980s when his family started getting priced out by rising rents. That’s when his dad remembered that his own father had once shown him the family’s racial land in nearby Kauʻula Valley. Equal to Palakiko’s grandfather, the family had been forced out by the Pioneer Mill sugar plantation, which had diverted the Palakikos’ water to gargle crops. Palakiko’s family still owned the title to the land, and his father was unswayable to find a way to reuse it.

First they cleared skim by wearing firebreaks and urgent the overgrowth, executive the flames with five-gallon buckets of water hauled from a nearby river. Once they had opened unbearable land to build a house, the Palakikos worked out a deal with Pioneer Mill to restore self-ruling water wangle to their property, connecting their home to the plantation’s water system with a series of 1½-inch plastic pipes.

Access to that water meant that the Palakikos could live on their racial land for the first time in generations. When then, Palakiko says, their property felt isolated from Lāhainā, wieldy only by old cane field roads that could take 45 minutes to reach town. But the family didn’t mind. It was unbearable to be worldly-wise to stay on Maui when so many other Native Hawaiians were forced by economic necessity to leave.

That isolation didn’t last. In 1999, Pioneer Mill harvested its last sugar crop, ending 138 years of cultivation in Lāhainā. The x-rated fields turned brown and Palakiko heard that the visitor was selling off thousands of acres. Where once the Palakikos had seen Filipino plantation workers tending to crops, they noticed fair-skinned strangers and surveyors exploring the fallow grounds.

The Palakikos soon realized that the land was now in the hands of Peter Martin, who had joined other local investors to buy everything he could of the old plantation land. These new owners soon subdivided the land and sold parcels at overly higher prices as demand for the zone known as Launiupoko kept increasing. It didn’t matter that the zone was zoned for agriculture: Like many other developers, Martin took wholesomeness of a legal provision that unliable homeowners to build luxurious estates on such land as long as they did some token farming of crops like fruit or flowers, no matter how perfunctory it might be.

By the time Martin finished the development, which included virtually 400 homes on virtually 1,000 acres, he was diverting scrutinizingly 4 million gallons from the stream every day, according to state data, scrutinizingly as much as the 4.8 million gallons Pioneer Mill had diverted each day surpassing it shut down.

Some days the Palakiko family would wake up to find no water running through the pipes. By the afternoon, puddles withal the stream would evaporate and fish would flummox on the hot rocks, suffocating. It wasn’t just the Palakikos who were suffering, but the whole river system: As Martin diverted water from the mountains, the waterway zestless up farther downstream, threatening the native fish and shrimp that lived in it. Palakiko appealed to Martin’s new water utility, Launiupoko Irrigation Company, but he said the visitor was hostile. First it tried to shut off the water the family had been receiving through plastic pipes, then asked the family to pay for water they’d unchangingly drawn for free, only relenting without the Palakikos fought back.

In wing to diverting water yonder from Native Hawaiian families, Martin has tried to gravity some from their land. In 2002, his Makila Land Visitor filed a so-called “quiet title” specimen versus the Kapus, flipside farming family whose land confines the Palakikos, seeking to claim a portion of the family’s racial land as its own. This legal strategy, which allows landowners to take tenancy of properties that may have multiple ownership claims, later gained notoriety when Mark Zuckerberg used it to consolidate his holdings on Kauai.

When the Kapus fought back, the visitor kept them in magistrate for scrutinizingly two decades, appealing over and over to proceeds the rights to a 3.4-acre parcel. The situation between Martin and the Kapu family became so tense that in 2020, Martin sought a restraining order versus one member of the family, Keeaumoku Kapu, accusing him of “verbally attack[ing] me with an expletive-laced tirade” and blocking Martin’s wangle to the disputed land. The magistrate imposed a bilateral injunction versus Martin and Kapu later that year; two years later, Kapu finally prevailed in court and secured the title to his property.

Martin’s companies filed multiple quiet-title lawsuits over the years as Martin sought to consolidate tenancy of the land virtually Launiupoko. Just without it began litigation versus the Kapus, Makila Land Visitor made a similar requirement versus a neighboring taro farmer named John Aquino, seeking to seize a portion of the land belonging to Aquino’s family. The company won the slice of land in an appellate magistrate in 2013, but the Aquino family stayed put. Police underdeveloped Aquino in 2020 without two of Martin’s employees crush a semi onto the land; Aquino had smashed the truck’s windows with a baseball bat. Makila later filed a trespassing lawsuit in 2021 versus Brandon and Tiara Ueki, who moreover live near the Kapus. The parties agreed to dismiss the specimen the pursuit year without an unveiled settlement. Increasingly recently, Martin has fanned plane increasingly frustration by selling properties with contested titles, prompting at least one ongoing legal battle.

Cory Lum / Grist

Meanwhile, Martin and his fellow investors sought to expand to other parts of West Maui with several large-scale developments in areas withal the coastline. In one instance, he and flipside pair of developers named Bill Frampton and Dave Ward proposed towers 1,500 homes, including both single and multifamily housing units, in the small beachfront town of Olowalu, plane though water wangle in the zone is minimal and rainfall is declining. The developers later scrapped the project pursuit protests from environmental activists, but in the meantime, Martin sold off a few dozen increasingly lots in Olowalu, where he has a home. He moreover created flipside utility, Olowalu Water Company, to supply homes in the zone with stream water.

Hawaiʻi, like most of the Western United States, allocates water using a “rights” system: A person or visitor can own the right to yank from a given water source, often on land they own, but they can’t own the water source itself. In states like Oregon and Arizona, this system has led to conflicts between settlers and tribal nations, but in Hawaiʻi the law provides explicit protection for Native Hawaiian users. State law stipulates that traditional and cultural uses, such as taro farming, “shall not be unexecuted or denied.” In times of shortage, Native users have the highest priority.

In 2018, the state water legation imposed so-called “flow standards” on several West Maui streams, capping the value of water that Launiupoko Irrigation Visitor and Olowalu Water Visitor could divert at any given time. Palakiko had mixed feelings well-nigh this: He didn’t want to sacrifice increasingly tenancy over the water that his family had used for generations, but it felt necessary in order to ensure someone could hold the companies accountable.

Even without these rules took effect, though, Martin’s water utility companies violated them dozens of times. When the state threatened to fine the companies, Launiupoko Irrigation Visitor stopped taking water from its stream completely. Residents of the lush Launiupoko subdivision soon had to ration irrigation water, and the Palakikos lost their wangle altogether. Their pipes stayed dry for increasingly than a week until a judge ordered Martin’s company to turn on the tap when on.

As the state croaky lanugo on stream diversions, Martin sought to secure increasingly water by tapping an aquifer underneath Lāhainā. Here again, he was accused of infringing on Native Hawaian cultural resources: When his West Maui Construction Visitor started digging a ditch for a water line in 2020, it excavated an zone that contained Native Hawaiian solemnities remains, triggering protests. Five Native Hawaiian women activists climbed into the company’s ditch to stop the construction project and were arrested. A judge later found the visitor broke the law by starting construction on the water line without all the requisite permits.

The new restrictions started to hamper Martin’s minutiae activities. Last year, his Launiupoko Water Visitor applied to the state’s utility regulator for permission to unhook water to a new zone near Lāhainā. The visitor said it had well-set to supply a nearby landowner with potable water for 11 new homes, and told the state it needed to increase its groundwater pumping by at least 65,000 gallons per day. The regulator rejected the expansion plan, saying the visitor had omitted “basic information” well-nigh where it would get this new water. The landowner that would have received the water was flipside visitor in which Martin has an ownership stake.

Even as his companies’ plans faced headwinds, Martin continued to benefit. He loaned Launiupoko Irrigation Visitor a total of $9 million in recent years as the visitor tried to expand its Lāhainā well system, charging 8 percent interest. The visitor tried in 2021 to secure a wall loan for the project, but three banks turned it down, with one noting that the company’s “interest payments to Pete” were “substantial.”

Glenn Tremble, a top executive at West Maui Land Company, the visitor at the part-way of Martin’s minutiae empire, said in response to a list of questions that Grist’s statements were “generally false and often libelous.” Tremble noted that Martin has built affordable housing units on West Maui and donated to churches. He said that Martin is “well positioned to squire with recovery and efforts to rebuild.”

If Martin’s track record with water and land made him infamous in Lāhainā, it moreover invigorated local support for plane stricter water controls. Palakiko’s long wayfarers for increasingly sustentation to the region’s water problems finally sink fruit last year when the state designated West Maui as a “water management area.” Instead of just setting limits on how much water Martin’s companies could take from West Maui streams at any given time, the state water legation spoken that it would revamp the area’s unshortened water system, giving highest priority to Indigenous cultural uses like taro farming. That may midpoint limiting wangle for Martin’s luxury developments, though Tremble disputes this.

“We’ve heard a lot from the polity well-nigh the minutiae of West Maui Land’s holdings in Launiupoko,” said Dean Uyeno, the interim chair of the state water commission, well-nigh the decision. “To protract towers in these types of ways is going to alimony taxing the resource.” The question, Uyeno said, is whether developers “can … find a way to [be] towers increasingly responsible minutiae that balances the resources we have.”

Martin thinks the treatise that water is a scarce resource is a “red herring.” He argues that the market is calling for increasingly housing, not increasingly water for native fish that rely on the streams.

“All the people [who] overly come to me say, ‘Peter, can you get me a house? I want a place to live,’” he said. “They don’t go, ‘Oh, I wish I had [shrimp] for dinner.’ That’s not what people tell me. They say, ‘Can’t you requite me some house, some land?’ I go, ‘I’d love to but the government won’t let me.’”

In the days surpassing the wildfire, Martin’s executives worked long hours in his West Maui Land Visitor office filling out 30 state applications justifying their current water usage and seeking more, in vibrations with the state’s revamp of the area’s water system. They submitted the applications just days surpassing the state’s August 7 deadline. The day without the deadline, Lāhainā burned.

To Martin, this is not a coincidence. He believes the state water commission’s efforts to increasingly strictly regulate water enabled the fire by preventing increasingly construction of homes with irrigated lawns — in other words, increasingly minutiae would have made West Maui increasingly resilient to fire. The day surpassing the water commissioners met in September, he wondered if the commissioners would unclose their responsibility for the wildfire deaths and regretted not pushing harder versus their restrictions.

“I finger I unquestionably have thoroughbred on my hands considering I didn’t fight nonflexible enough,” he said.

There’s no vestige that the state management rules, which are still in the process of going into effect, had any validness on the fire. When Grist relayed this treatise to the interim leader of the state’s water commission, he was stunned.

“That unquestionably leaves me speechless,” said Uyeno. “I don’t know how to respond to that.”

Palakiko and his family spent the day of the fire watching the smoke rising from the coastline, watering the grass on their property and praying the winds wouldn’t shift, sending the flames their way. Five years earlier, flipside fire fueled by a passing hurricane had burned lanugo two homes on their land.

That day, their prayers were answered. But when Palakiko’s son, a firefighter, came home shaken from his shift fighting the blaze, the family realized that the West Maui they had known their whole lives was gone.

Two days later, Palakiko received flipside shock when he read Tremble’s letter accusing Kaleo Manuel, the deputy director of the water commission, of delaying the release of firefighting water. The letter argued that Manuel had waited to release water to West Maui Land Company’s reservoir until he had checked with the owners of a downstream taro farm. That sublet belongs to the Palakikos.

The company’s allegations were explosive. The state shyster unstipulated launched an investigation and requested that the legation reassign Manuel, who had been instrumental in establishing the Lāhainā water management zone and was the only Native Hawaiian to overly hold that position. Governor Josh Untried temporarily suspended the rules that limit how much water Martin’s companies and other water users can yank from West Maui streams. The state later reinstated Manuel and restored the rules. In a statement to Grist, Tremble said he respects Manuel’s “commitment and his integrity” and said that “the problem is the process, or lack thereof, to provide water to Maui Fire Department and to the community.”

While there was no vestige that filling the reservoir would have stopped the fire from destroying Lāhainā, and firefighting helicopters wouldn’t have been worldly-wise to wangle the reservoir due to upper winds on the day in question, there’s a growing consensus among scientists in Hawaiʻi that one factor in its rapid spread was the proliferation of nonnative grasses on former plantation lands — including lands that Peter Martin owns.

Before the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893, surpassing the dominance of the sugar industry unliable plantations to divert West Maui’s streams, Hawaiian royalty lived on a sandbar in the midst of a large fishpond within a 14-acre wetland in Lāhainā, which was known as the Venice of the Pacific.

After plantation owners diverted streams for their crops, the royal fishpond became a stagnant marsh, and later was filled with coral rubble and paved over. Now, Palakiko imagines what it would be like if the streams were unliable to resume their original paths: what trees would grow, what native grass could flourish, what fires might be stopped. He doesn’t think this vision is at odds with the need to write Maui’s housing crisis.

For Palakiko, the fight over the future of water in Lāhainā is well-nigh increasingly than just who controls the streams in this section of Maui. It’s moreover in some ways a referendum on what future Hawaiʻi will choose: one that reflects the worldview of people like Palakiko, who see water as a sacred resource to be preserved, or that of people like Martin, who sees it as a tool to be used for profit.

To Martin, such a shift is unsettling.

“I mean, for a hundred years, you could take all the water, and all of a sudden these guys come in, and say, ‘Oh, you can’t take any water,'” Martin said. “And they made it sound like I’m this terrible person.”

This story has been corrected to reflect the updated death toll provided by Maui County.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The libertarian developer looming over West Maui’s water conflict on Nov 27, 2023.